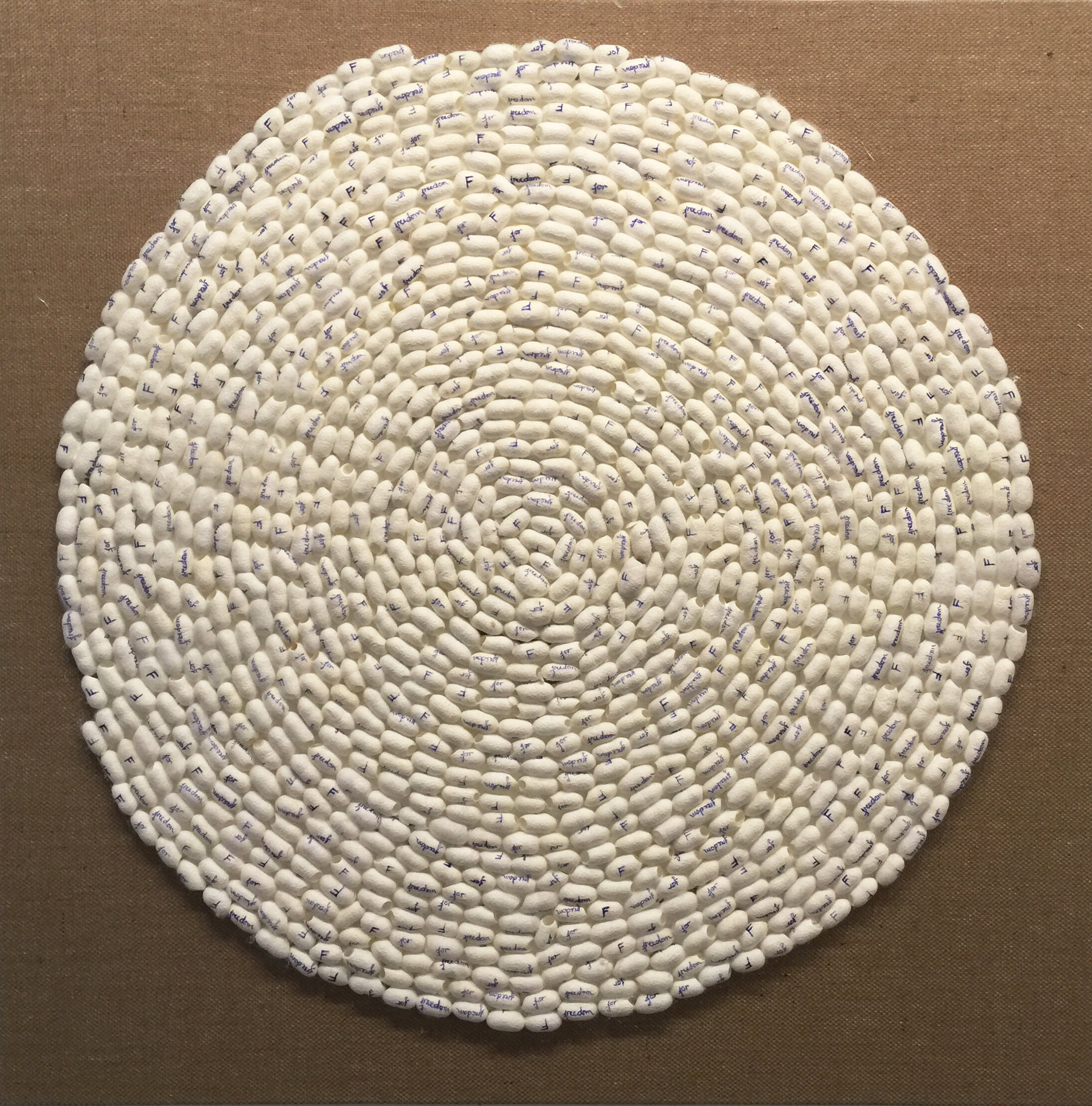

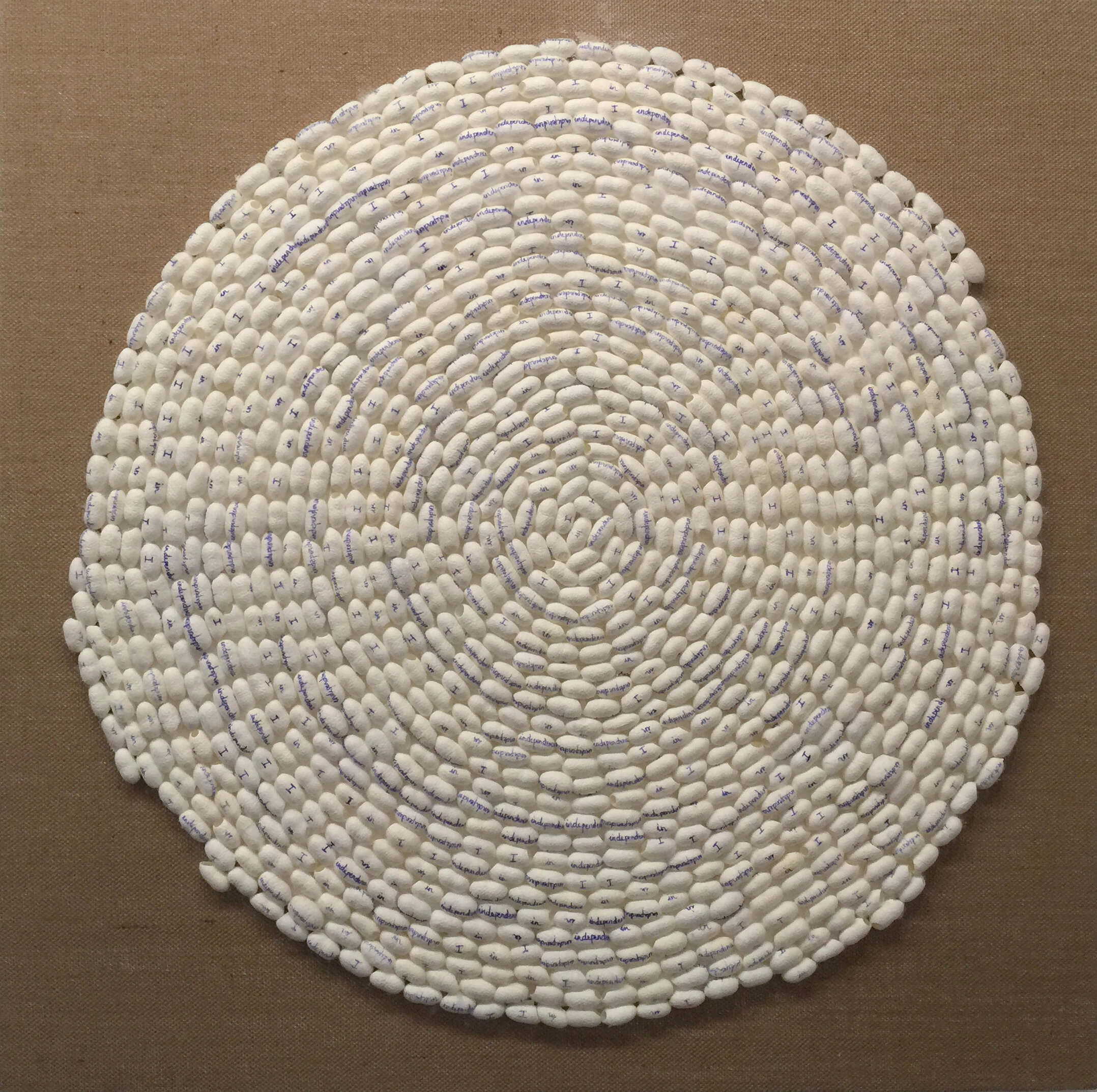

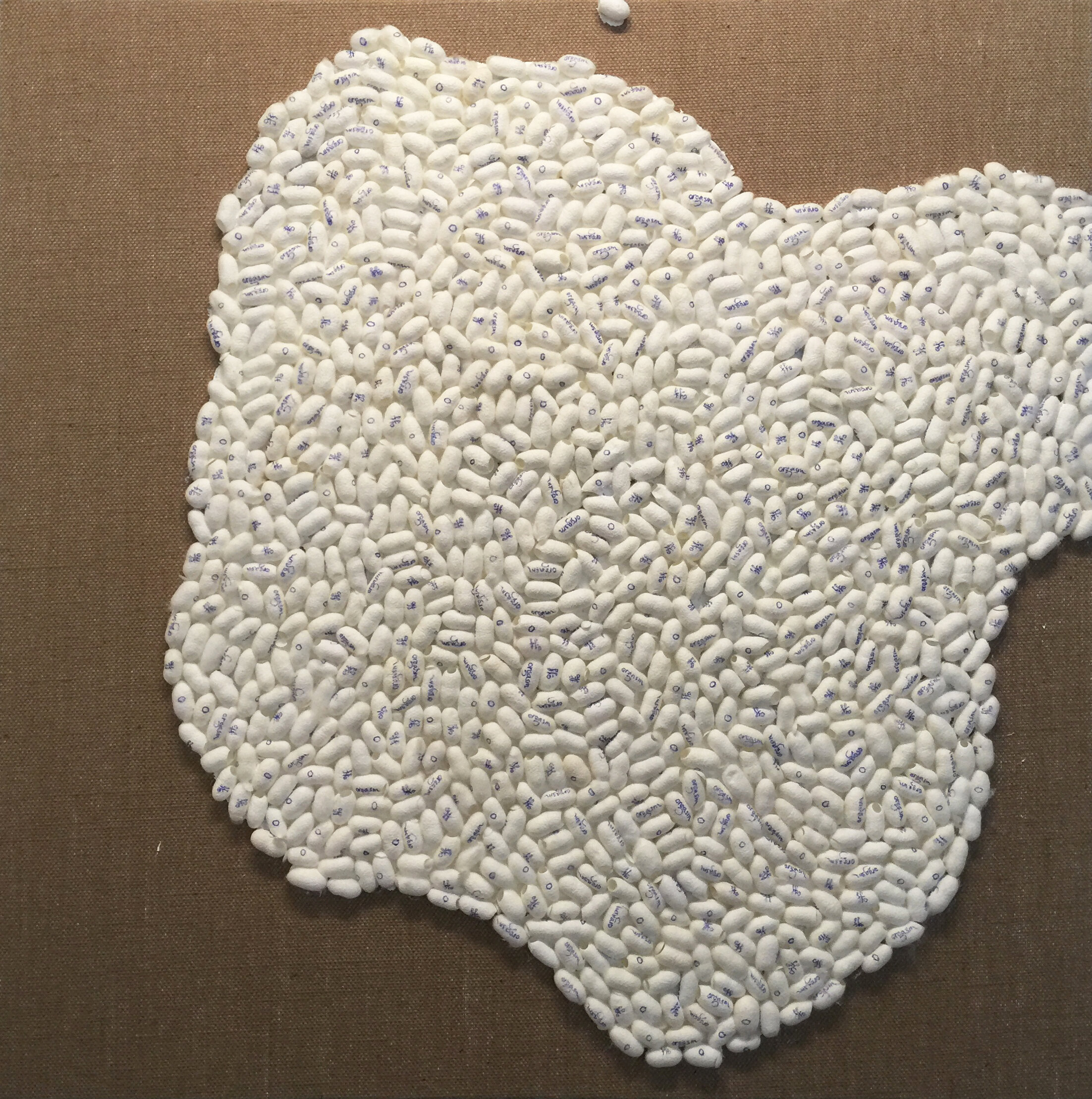

Freedom, Independence, Orgasm

silk cocoons project

2018-ongoing

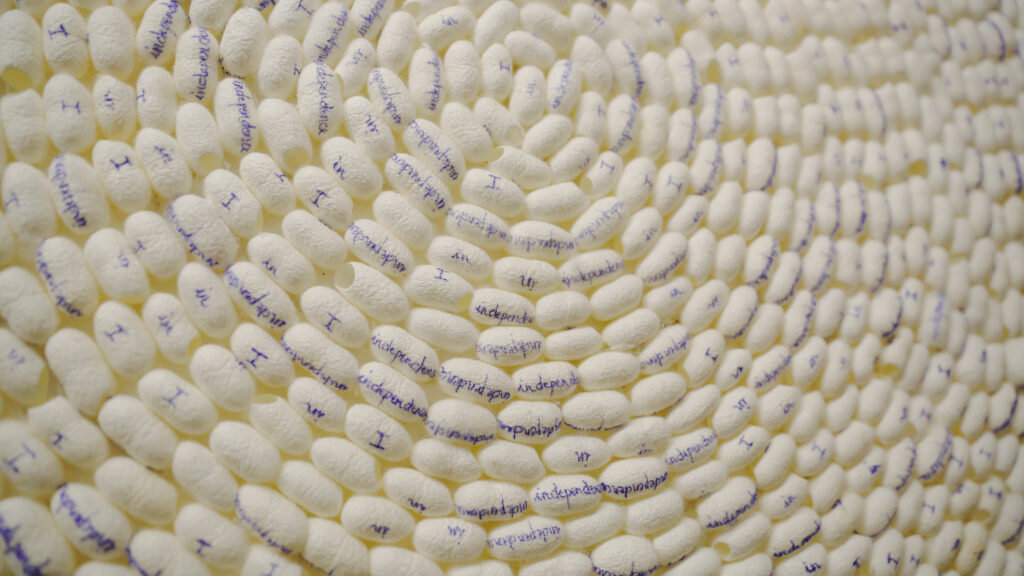

marker on silk cocoons, canvas.

FREEDOM, INDEPENDENCE, ORGASM

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness Độc lập, Tự do, Hạnh phúc Live, Laugh, Love Just Do It

Cam Xanh’s Freedom, Independence, Orgasm (FIO) immediately joins ranks with the litany of crisp slogans that define nations, movements, and people. Vietnam’s national take on this—translated to ‘Freedom, Independence, Happiness—bears a strange and obvious resemblance to those of the two western nations that most forcefully repressed Vietnamese independence. These mottos work strangely, and often contradictorily. Brevity imparts gravity to each word. Freedom and independence are included despite their very similar meanings. In just these two words, a rift between personal freedom and national independence is exposed. Struggles for state independence so often infringe on citizens’ freedoms: forced conscription, income taxes, and trade tariffs come to mind. The glaring ‘orgasm’ presses this further, pointing to the self-serving, shortsighted, and all-too-brief pleasures that lie beneath so many beneficent utopian imaginings, while also disrupting the sober air typical of similar incantations. FIO is most concerned with words, and tasks itself to break apart the mantric power that certain arrangements of words gain through repetition.

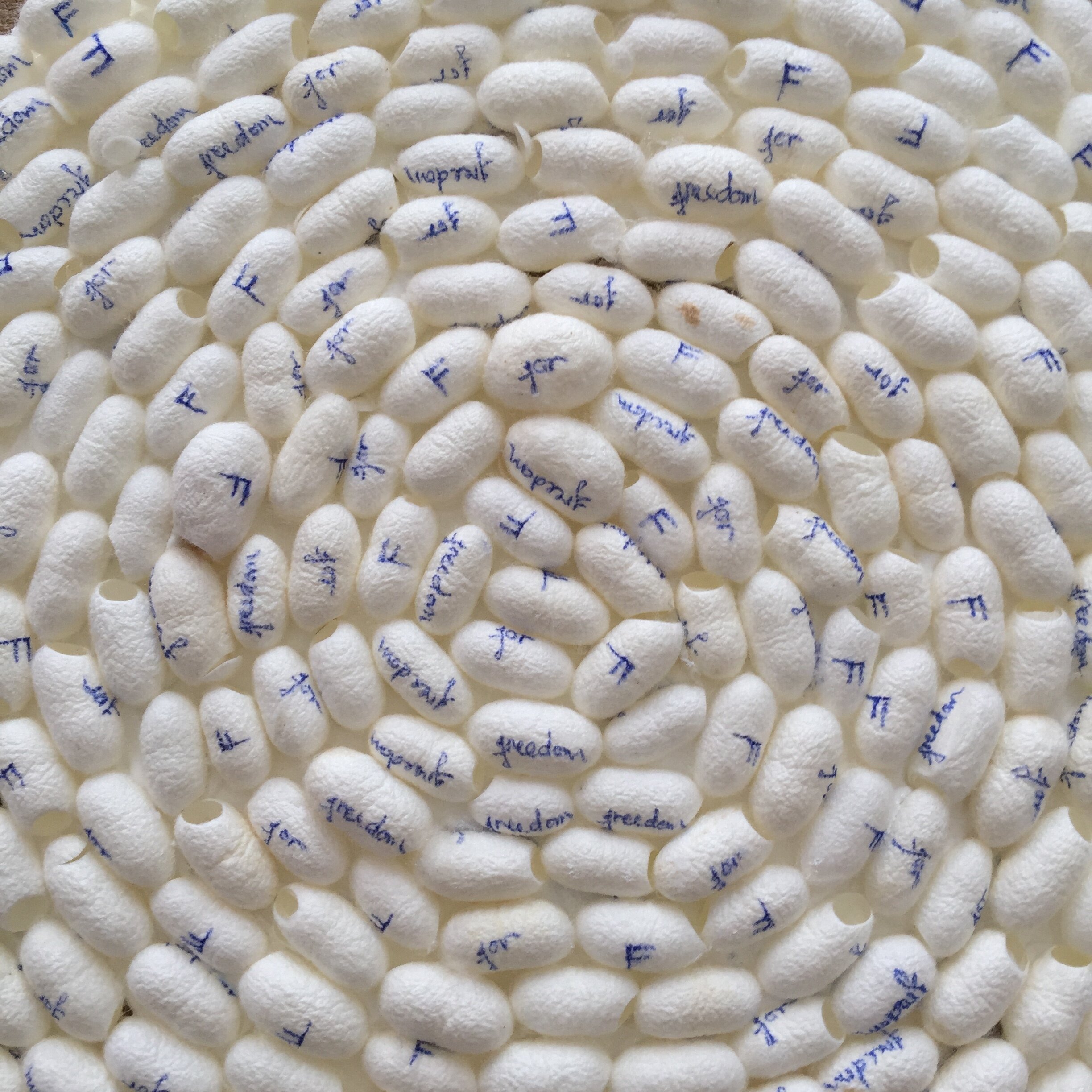

Her first amendment is to add a capital letter and preposition to each of the three nouns. These solemn lofty ideals suddenly resemble a children’s book: F for Freedom, I in Independence, O off Orgasm. Each word is built into its own mantra, one into which the original word itself can easily disappear without notice. The words are then multiplied and indiscriminately reassembled. New sentences emerge (‘F for F’, ‘Orgasm Off’, ‘Independence in Independence’), and their obvious dearth of content latches onto the original text, as “F for Freedom” appears right next to “for F Freedom.”

Cam Xanh’s text, altered in content and repurposed to emphasise its insignificance, acts like a lighthearted iconoclast—much like the artist herself. But where the text imparts jocularity and lack of content, her visual arrangements convey the grave power these words carry in the world. The work is in fact a graveyard, composed of three canvasses with roughly 1000 silkworm cocoons on each. Inside each cocoon was a worm that has been boiled, as in commercial silk production. Cam Xanh has killed thousands of worms for her series of cocoon pieces and the three canvasses composing FIO reveal this cost. Square, unframed, raw canvasses expose the silk-white cocoons. Left to themselves, their overlapping shadows create a kinetic depth, while the blue-ink word written on each keeps the cocoons from forming an innumerable mass. Rather, it is very apparent that the work is composed of thousands of pieces, and expanses of yet unused canvass suggest plenty of room to accommodate more casualties.

As the text and the medium work between buoyancy and gravity, the natural beauty of the cocoons—their whiteness, contours, the paths and textures they weave on the canvass—is balanced by a foul mechanical context. The worm’s life, until it acquires its wings, is clearly determined. It is first an eating machine, devouring mulberry trees. One month later, it becomes a silk machine; for days, it moves only its head rhythmically while salivating its to-be cocoon. Finally, the mysterious metamorphic process can commence, but it is also at this point that productive forces outside of the worm intervene. The worms are mass-harvested, mass-boiled, and mass-disassembled into luxury fabrics, or artworks. Cam Xanh orders thousands of worms and becomes a writing machine.

Unfortunately, she is a machine with a distinct distaste for the raw materials at hand.

Her childhood aversion to the worms and their cocoons has gained momentum with age, to the point of phobia. And yet the work’s concept demands that she individually mark each silk vessel. She compares it to the punishment of writing lines at school; each repetition internalises the message but also reveals its dependence on being mindlessly echoed.

The result of all of this, FIO, can be seen as the worms’ “getting their wings” after all. Rather than as silk, where each thread dissolves into the mass of threads, their rebirth in FIO still recalls the life that brought them to the canvass. Patterns emerge and disappear, fleeting but continuously, like a moth in the wind, imparting movement to the deceased.

Text, context, and image are ultimately unified. Carcasses decorated with slogans reiterate the lethal power of words. But there is more relating worms to humans, alive and dead. The mechanical, distasteful process of creating the piece: labor. The distribution of the cocoons, with hardly any room between each other, but with plenty of room to grow in number: cities, graveyards, assembly halls. The dead silkworms: casualties of wars and personal conflicts sparked by conflicting ideals. FIO is not a work of peace, as it is predicated on exploitative, bodily death. It merely partakes in and describes a process. It begins with three childish but fundamental concepts, which, as they gain momentum and volume, lose their literal significance. But the casualties of the past are then absorbed by the concept-words; memory, history, and emotion compensate for the mangled text. More casualties will only further reinforce this, just as they would continue to aggrandise FIO itself. There are, after all, plenty more worms, and there is plenty of space to continue.