f for fake

2013 - 2014

installation

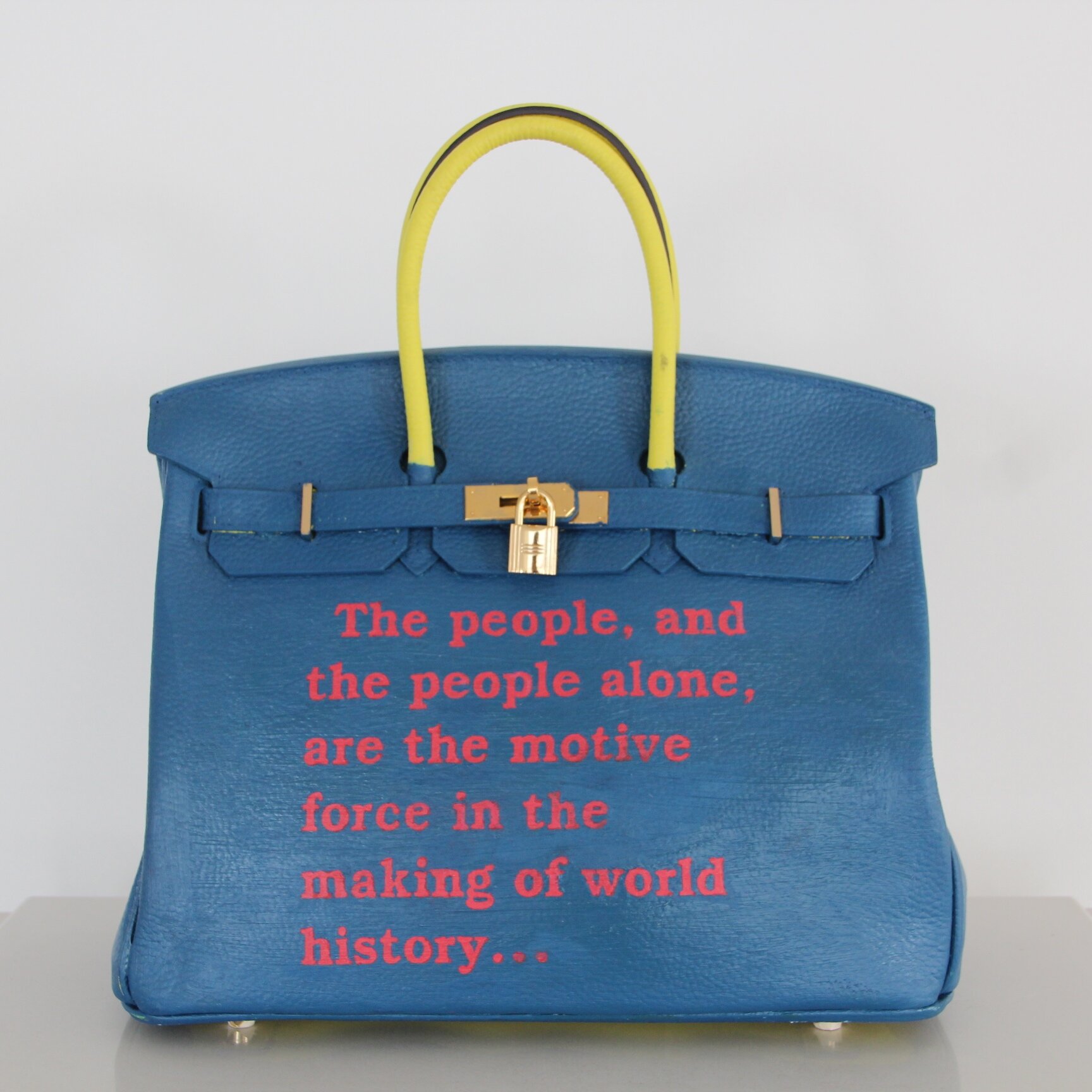

oil on fake birkin bag, covered in epoxy

F for Fake

It is fitting that Cam Xanh’s anti-ode to the lionised Hermès Birkin bag is being exhibited for the first time following the year of ‘post-truth’, for the question of what is real and what is fake has never been more relevant. Extremely hard to buy and excessively expensive (retailing for between $10,000 - $200,000 USD, with high-quality fakes costing up to $2,000), the Birkin has become a symbol of not only wealth but an exclusive class of people well-connected enough to own one. They are their own economy and, real or fake, possess their own politics. It is this exactly this iconography that Cam Xanh seeks to undermine, as the undercurrent of dark humour that is rife throughout her work comes to the forefront in the F for Fake series. Cam Xanh’s Birkins are explicit in their duplicity: painted over and covered in a clear epoxy resin, you can quite literally see through their deceit. Though conceived as part of a larger series, the trio tells a disturbing story that fuses cultural and political histories with contemporary anxieties. Aligned by their shared focus on the growth of Communism and its spread eastward, Cam Xanh uses the Birkin bags to discuss and invert wider themes of manipulation by politics and propaganda, advertising, and art.

Cam Xanh takes the idea of a ‘genuine-fake’, a fake just as good as the real thing, to its extreme by partnering with an art forger to reproduce famous images on each bag. The first bag reads “Als Ich chan ..”, a tribute to the late Dutch painter Jan van Eyck. Roughly translated as ‘As I can’, the statement appears on the frame of van Eyck supposed self-portrait, Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (1433). The self-portrait, featured on the reverse of the bag, is considered van Eyck’s declaration of his painterly capability to the world. A master of deception himself, van Eyck is revered for his control of oil paints to create a striking false sense of depth in his work. One of the first painters to include a signature on his work, van Eyck’s personal motto – ‘As I can’ – is indicative of his confidence in his abilities, as well as his position as one of the most dominating and influential painters of his time. However, Cam Xanh exploits this reputation by substituting van Eyck’s face for the uncannily similar Vladimir Putin’s in her own playful style. Instead of meeting the painter’s assertive gaze, we come face-to-face with Russia’s President Putin, a man equally self-assured and authoritative in his actions. Conceived just before Putin’s take over of the Crimea in 2014, Cam Xanh’s piece lampoons this sense of entitlement, destroying the aura of Putin as an icon of strength and power; Putin is no longer the aggressor, but has instead been made the victimised subject of her work – the manipulator has become the manipulated.

Just as Putin appears cloaked in the disguise of van Eyck’s self portrait, so too does the second bag’s Princess Anastasia, dressed in the clothes of a labourer. Cam Xanh plays with the paradox of this impersonation in reproducing it on fake Birkin; Anastasia wears the clothes of the poor as a means to hide and survive, whilst descendants of communist leaders today can be seen wearing comically expensive fashion merchandise. For in 2017 it is money, not heritage, that births modern ‘princesses’. The subject of the centre bag, Putin and Lenin enclose ominously on either side of a startled looking Anastasia from Disney’s animated film: her cartoon rendering emphasising the fiction of her rescue as an escapist fairy tale. The idea that the innocent, young princess might have survived the persecution that killed her family instead transpires as a romantic notion that distracts viewers from the harsher reality of Communism’s troubled past. Anastasia can subsequently be interpreted as a symbolic victim for others who have lost their lives in the pursuit or defence of an ideology. On the reverse of the bag, Cam Xanh’s reference to Barnett Newman’s colour field paintings “Who’s afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue” reinforces this position. Newman’s title is sinister not only in its insinuation of ‘The Big Bad Wolf’, but also his own personal background as a Jewish painter who addressed themes of the holocaust in his works. Together, Cam Xanh successfully combines these cultural references to alienate and remind her viewers of their impotency and position as spectators to world wars, genocides, and executions both past and present.

Last in the trio comes Lenin, stiff in his mausoleum, and he too is costumed: a painted corpse dressed up by another as a sleeping man. The effect is eerie and macabre alongside a youthful Anastasia whose own death he was implicated in. Ever jovial, Cam Xanh’s both exalts and destabilises Lenin as an idolised figure by using his doctrines in her work. Rather than protected being protected by the bags, the texts are instead torn apart, their power destroyed, and used as bag padding just as street sellers fill their fakes with scrap paper – yesterday’s news. Large flowers blossom out of the darkness surrounding Lenin, as though marking his grave, but the bloodied drips leaking from the red petals only incriminate him further. The flowers themselves pay homage to Cy Twombly’s 2007-08 flower paintings and the flower’s ability, like art, to be laden heavy with symbolism. Twombly and Cam Xanh both use their works in this way to create sites of memory, where viewers can engage with shared cultural histories. Artworks become a place where collective guilt is both acknowledged and purged, a medium that recollects the past. Questions of life and regret are raised. At his death, did Lenin feel his actions were justified? Did he feel remorse for the sacrifices he endorsed? The significance of the flowers goes further than their connotations of blood and the grave. “Let a hundred flowers bloom,” said Chairman Mao, founder of the communist People’s Republic of China, “let a hundred schools of thought contend.” The subsequent tyranny of Mao’s regime that followed in the wake of the Hundred Flowers Movement becomes the alternative subject of the third piece. The association with Mao’s malicious deception brings forth feelings of being lied to and a false sense of security that lingers with her viewers.

Conceptually, Cam Xanh’s goal is that of an intellectual rebirth: her works a result of a search for how to manipulate the information that has manipulated our pasts and presents. Her work encourages us to look past the information we receive from politicians, brands, artists, and art critics, to see the agenda behind it and remind us of ourselves as individuals. Her presentation of fake Birkins simultaneously forces us to question the true value of real ones they imitate. Does owning an authentic handbag make you a more authentic person? Cam Xanh pushes us towards the absurd through her ridicule of consumerism. They expose the instability of ascribed value versus intrinsic worth: to attribute self-worth in such a way means you are buying into a constructed ideal, borrowing your identity, wearing it on your arm.

The title of the series F for Fake, comes from the documentary film essay from Orson Wells of the same name. In it Wells explores the life and career of Elmyr de Hory, a professional art forger, and investigates the boundaries of authorship and authenticity especially in relation to art and how we value it. For Cam Xanh and Wells alike, art is another form of manipulation at work in the world. The film ends with a statement from Pablo Picasso that highlights how both Cam Xanh and Wells both use their works to play with the concept of truth itself: “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.” For Cam Xanh, the desire to create art comes from an urgent need to make sense from nonsense but is also an experiment in conceptual thinking and production. Using an art forger manifests this theme and subverts traditional conceptions of art production. Cam Xanh creates value with her work where there was less – perhaps none – before, blurring the line between high and low art just as the existence of fake merchandise erode definitions between high and low fashion.

Ultimately, Cam Xanh’s work concludes almost apolitically. The individual, the viewers themselves, can be interpreted as the fundamental subject of her work. Under the story of each bag remains the inauthentic Birkin; the bags therefore become a visual metaphor for the lies and deceit of a wider political struggle and abuses of power by the state. We the viewers are urged to find and claim our autonomy as individuals, and see through the manipulations of politicians that would implicate us in actions we might otherwise oppose.

< Maria Sowter >